Even as a high schooler in Kathmandu, my overriding reason to pursue a career in medicine was to serve the needy and poor. It was my good fortune that I was able to complete graduate medical education on a scholarship in India and move on to the US to complete a surgical residency program in Orthopaedic Surgery. Landing in New York with $50 in my pocket and being very poorly informed about living in such a vast city was nothing short of an adventure! The challenges were enormous but my determination to move on and succeed was strong. The training experience was unique and brutal – it rubbed into my being the meaning of perseverance and hard work. I was lucky to complete my residency in the subject of my choice.

Halfway around the world my parents lived in a village in their traditional farm – a simple life very close to nature. An occasional letter would arrive from them with suggestions about giving work in Nepal a try. This thought did keep creeping into the back of my mind.

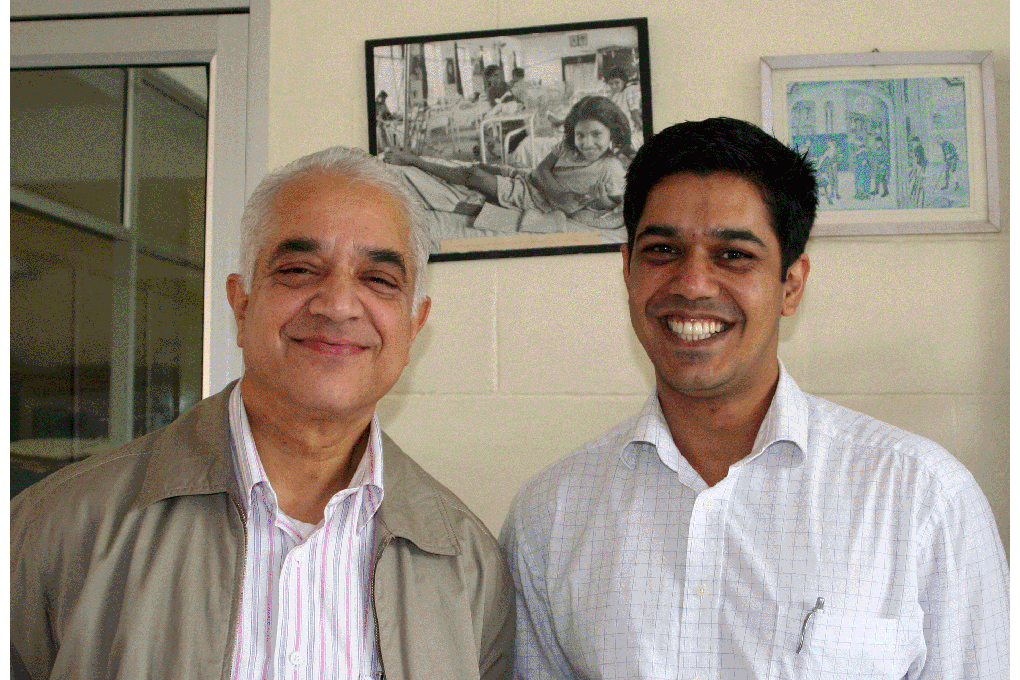

As I neared the completion of my training, I came to understand the complexities of advancing one’s career in the US. There would be no looking back to return to Nepal for a go at work there if I didn’t do it now! My wife and our little son Anil returned to Nepal 10 months ahead of me, so that on completion of my residency I could prepare for my examinations. Thus, I was not present when our second child, Dr. Bibek, was born. I saw him only eight months after his birth when I returned to Nepal. Once back, I did not know what to expect professionally. My intention was to be useful and give it my best try or return back to the US.

Soon after returning, I realized that I had made a grave mistake by not continuing to pursue a career in the US – at least this was my initial feeling. There were no jobs to walk into, no platforms for work. The hospitals that existed were primitive and very poorly equipped. Amidst such depressing facts, I started work as a volunteer surgeon at a Mission Hospital literally working out of a box of basic supplies. I also had to simultaneously deliver anesthesia and assist other surgeons. I switched many gears, I lived in poverty – I was unable to deliver any comforts to my family. I walked or rode an old bicycle to work, and I feared at times that I had failed.

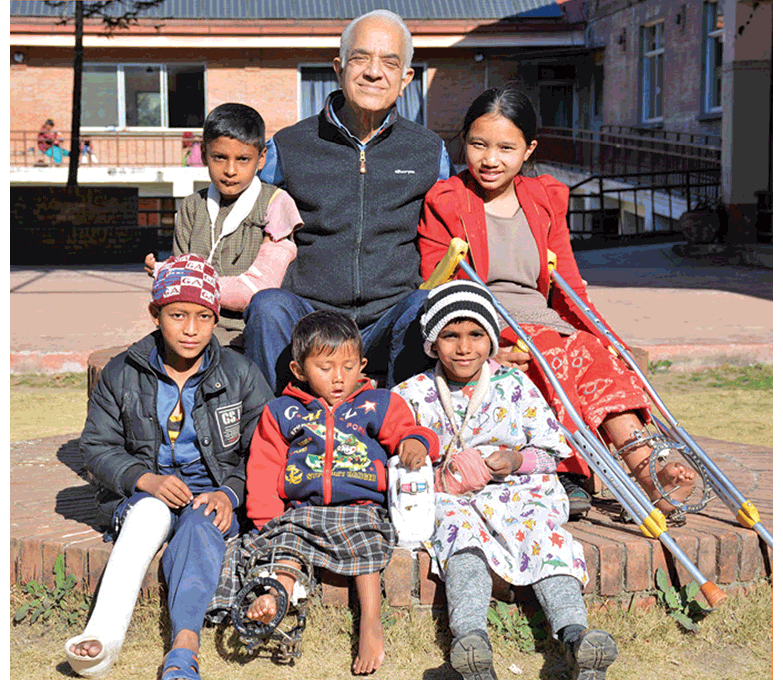

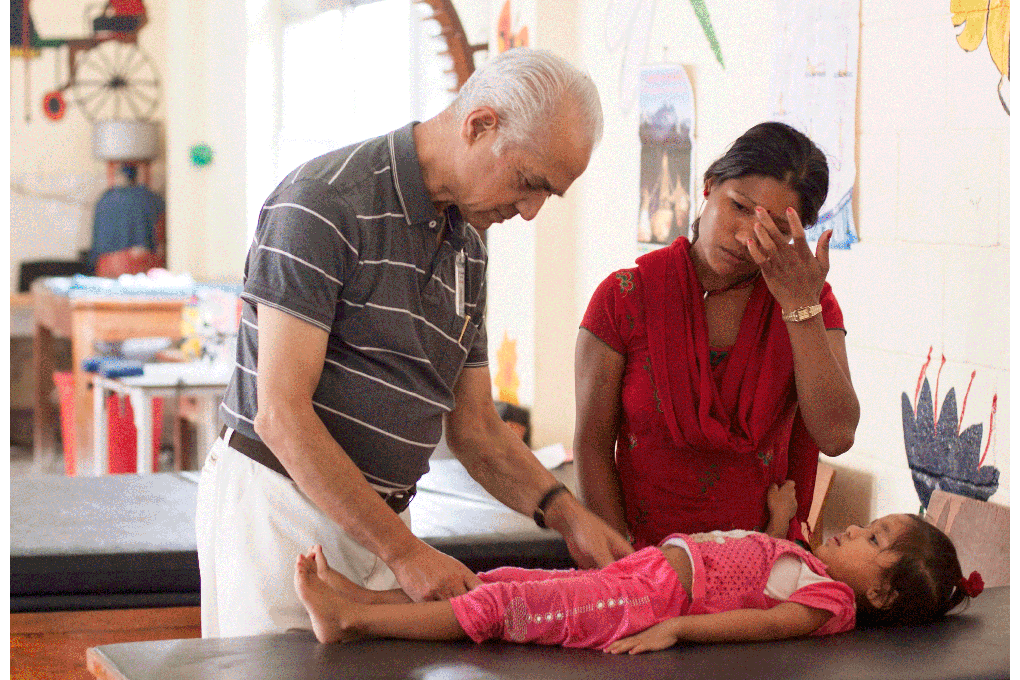

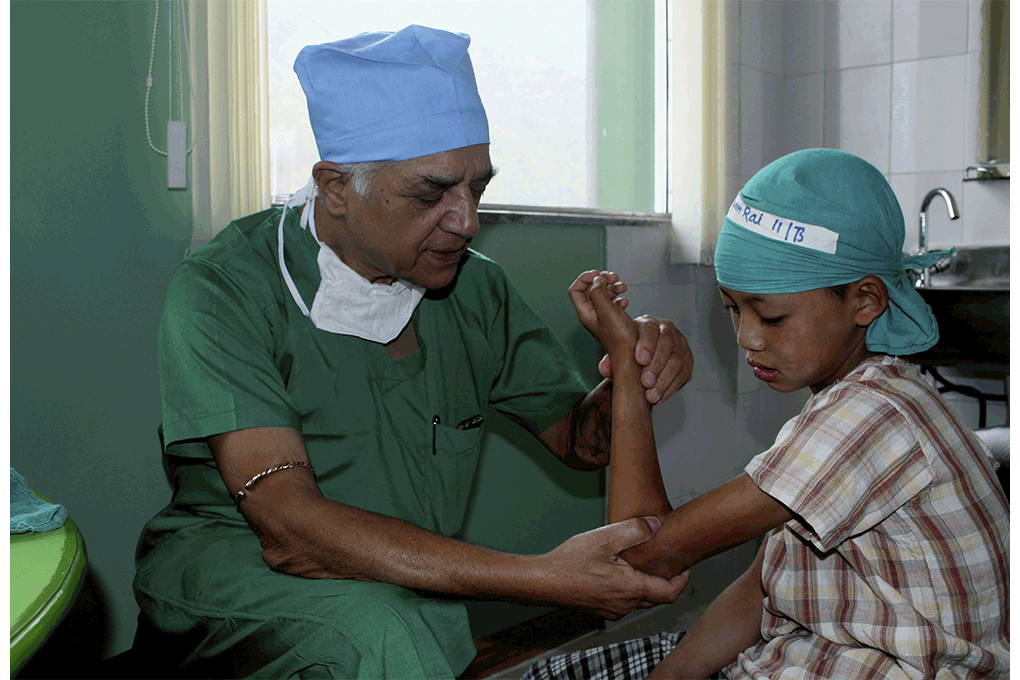

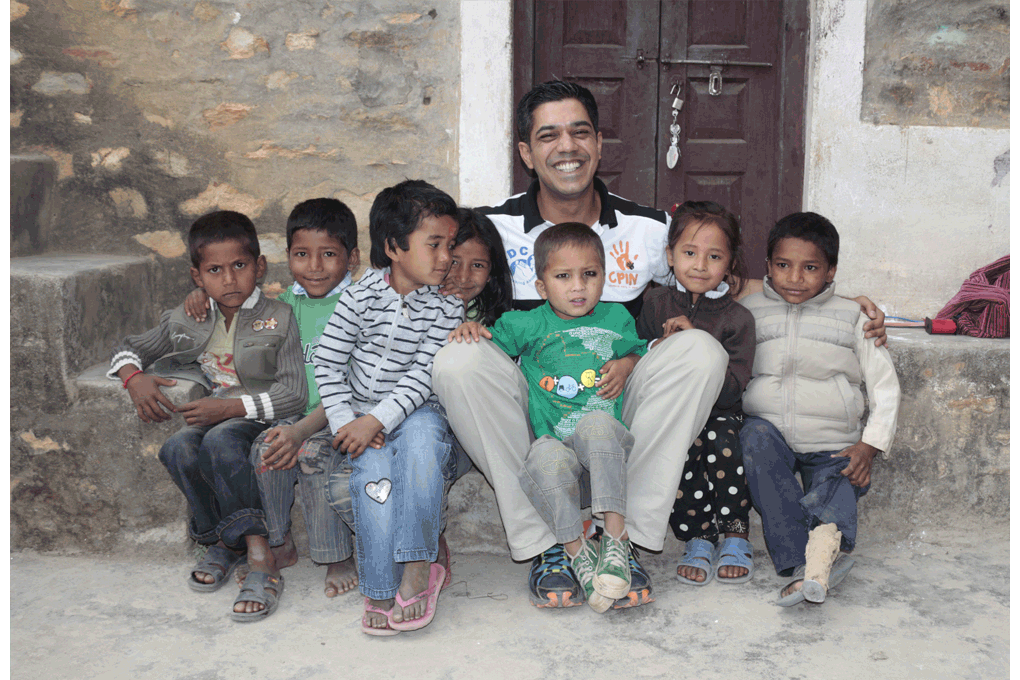

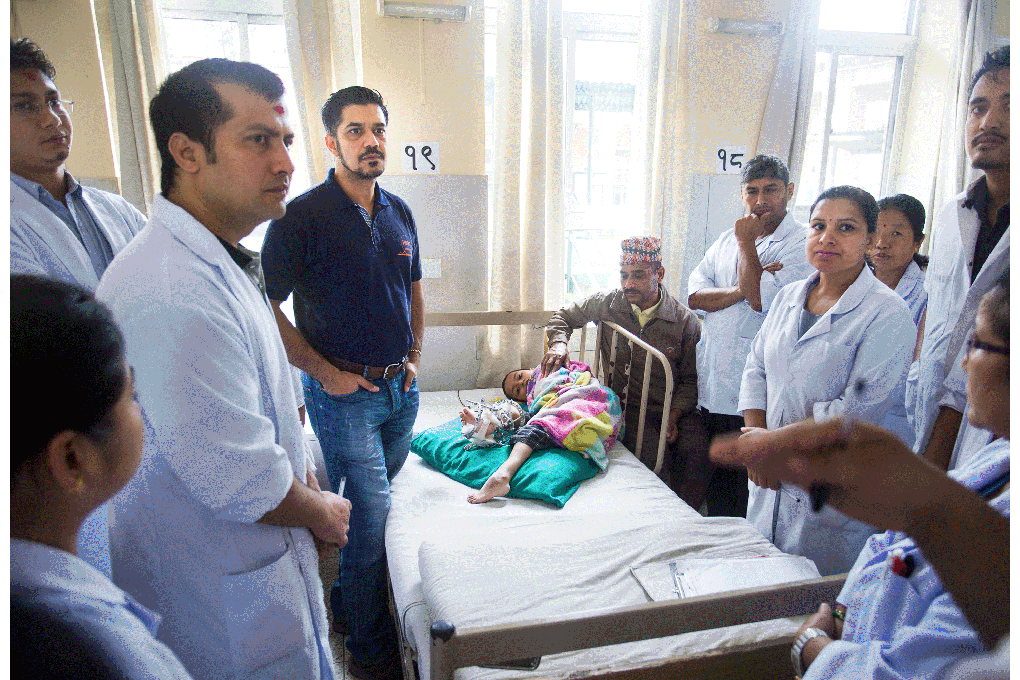

As the months went by, the obstacles that I was facing on a daily basis unfolded into many heart-wrenching stories which started to affect me. Children having to leave home to work, children suffering from deformities, diseases, and injuries because no treatment was available, or it was unaffordable. These early experiences haunted me in the daytime and in sleep, and motivated me to do more. I volunteered as a hand surgeon at a Leprosy hospital one day a week; another day I volunteered at a hospital 20 km outside Kathmandu in Banepa. I also worked at a home for physically handicapped children run by a Jesuit missionary priest. I was appalled as well as overwhelmed by the total inadequacy of services available. Here was an opportunity to be a real changemaker and help the needy. These experiences completely changed my attitude and I made a determination that I would make every effort to create better platforms for care in whatever way I could.

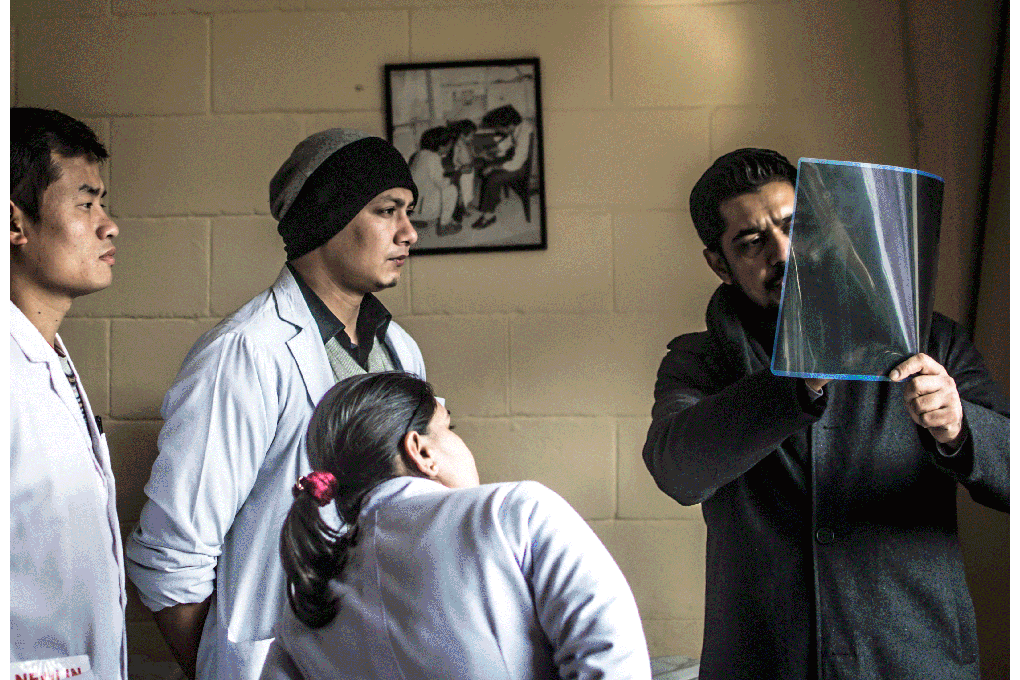

My confidence grew as I became more familiar with the prevailing pathologies – I also started to improvise and quickly realized how so much could be done for so little, despite very primitive conditions in the facilities where I was working. I was sold – the idea of going back to the US disappeared from my mind completely.

Opportunities did come, along with hard work. HRDC was born in 1985 and I took on the challenge of running it with very limited resources. I practically lived in the hospital day and night for several years. I was able to realize the importance of developing manpower for sustainability of the work. Partnerships developed and strengthened; residency training was begun. Thirty-five years on HRDC has blossomed into a unique facility unlike anywhere else in the world, providing the best comprehensive care to the neediest children.